INTRODUCTION

In Canadian midwifery, quality care is defined as safe, effective, and person-centered, rooted in trust and collaboration between midwife and client.1–5 Although provincial midwifery scopes of practice vary, the Canadian Association of Midwives (CAM) recognizes informed choice as a fundamental tenet.4,5 Informed choice empowers clients, establishes trust, and fosters a collaborative midwife–client relationship that ultimately contributes to a client’s perception of their care.6,7

Yet, when clients choose to diverge from clinical recommendations, research shows that quality of care often declines and may result in coercion or mistreatment.7–9 Midwives, particularly those who are inexperienced or have less confidence, report ethical uncertainty in these situations.10–13 Without an explicit decision-support tool or framework, midwives must navigate the clinical, ethical, and relational complexities involved without structured guidance—conditions that can heighten moral distress and increase the risk of undermining client autonomy.10,14

We address this gap by proposing a midwifery-led, Canadian-specific solution: the Perinatal Midwifery Care Plan (PMCP) and its framework. Grounded in the concept of relational autonomy, the PMCP supports transparent, values-based dialogue, and consistent documentation when care diverges from recommendations.

INFORMED CHOICE IN MIDWIFERY: FROM CONSENT TO RELATIONAL AUTONOMY

Although often used interchangeably in literature, it is important to note that informed choice and informed consent are not synonymous. Informed consent is primarily centered on the legal process and the client’s agreement to a prescribed plan, rather than being solely rooted in client autonomy.15 In Canada, the provincial consent acts serve as the primary legal framework for midwives, outlining subjective criteria such as a patient’s competence, the availability of reasonable options, full disclosure of relevant information, and freedom from coercion.15,16 However, informed consent falls short by omitting a crucial component: alignment with a client’s beliefs and values.

In contrast, informed choice places emphasis on promoting and supporting choices that resonate with a client’s beliefs and values.14,17,18 Bioethicists have long argued that informed choice should be the aspiration of healthcare systems, as it better reflects and supports client autonomy.17,18 In the context of midwifery, informed choice is foundational to the development of trust and a respectful midwife–client relationship, significantly impacting a client’s perception of quality midwifery care.4,7–9

Therefore, to further develop the concept of autonomy in midwifery, it is important to move beyond individualistic models and consider a relational understanding of autonomy.6,14,19 Relational autonomy recognizes that individuals make choices within a web of relationships, shaped by social, cultural, economic, and institutional contexts. This framework complements midwifery care, which already centers relationships, continuity, and shared decision-making.5 It challenges the idea that autonomy is expressed solely through detached rationalism and acknowledges the deeply contextual and collaborative nature of informed choice decisions in healthcare. Within this model, respecting a client’s autonomy includes considering their lived realities, cultural norms, and support systems, rather than framing decisions as entirely independent.6,14,19

Amidst these considerations, midwives are entrusted with the responsibility of promoting and upholding a client’s autonomy, shaped by a comprehensive understanding of their beliefs, and values.1–4 During each prenatal visit, informed choice discussions are typically led by midwives, covering topics such as antenatal screenings (e.g., ultrasound), intrapartum care (e.g., choice of birthplace, pain management, and support person), and postpartum care (e.g., newborn screenings, feeding options).20 These informed choice discussions must encompass all necessary information, such as medical and social risks, to allow a client to make a decision that aligns with their beliefs, values, and goals.17,18

The midwife’s responsibility lies not in determining what is best for the client but in facilitating the journey toward making decisions that align with the client’s own beliefs and values.4 In this sense, the midwife’s ethical role is not that of a neutral informant or authoritative enforcer but that of a skilled facilitator of meaningful decision-making, who fosters dialogue, supports reflection, and respects relational autonomy. Although CAM emphasizes the significance of informed choice and a client’s right to choose, there remains a lack of explicit guidance for navigating situations where a client chooses care that differs from clinical recommendations.10–13

Research shows that midwives with confidence gained from professional experience are better equipped to support clients in making informed decisions, particularly when those decisions diverge from clinical guidelines.21 These midwives use effective communication and collaborative negotiation to uphold autonomy while maintaining safety.21 However, this skillset—rooted in empathy, adaptability, and individualized care—is often not explicitly taught in Canadian midwifery programs but instead develops through informal learning, such as apprenticeship or mentorship.10,12 Without such guidance, situations in which clients choose care outside of guidelines often become framed in terms of the medical–legal risks to the midwife.9,10,12 This can shift the focus toward documenting the encounter as a form of professional protection, rather than engaging in open, values-based dialogue.10,12 While this defensive approach may safeguard the provider, it can also create conditions for coercive practice, ultimately undermining client autonomy.7–9

Ultimately, while relational autonomy offers a compelling ethical foundation for midwifery care, its translation into everyday practice is complicated by systemic, institutional, and interpersonal challenges.11,13,14

CHALLENGES IN SUPPORTING INFORMED CHOICE

The midwife–client relationship, pivotal in the provision of quality care, may face negative repercussions when midwives experience stress stemming from a client’s decision to pursue a care path that differs from recommendations.10–12 These discussions can evoke significant emotional strain and often give rise to informal coercion, defined as any practice that pressures a client into a decision without the use of overt force or formal authority. This may include guilt-tripping, fear appeals, or the withdrawal of emotional or clinical support.7–9 Specific examples reported in the literature include dismissing client concerns, ignoring expressions of fear or pain, or offering care options under time constraints with limited explanation.8–10 In more severe cases, clients report verbal threats such as being told they are “endangering their baby” or being abandoned by providers unwilling to support a client’s decision.8–10 When employed, these actions can strain the midwife–client relationship and undermine trust, key pillars in respectful and autonomous care.8,9 These tactics not only violate informed choice but also erode the principles of relational autonomy, which calls for decisions to be made through supportive dialogue that is sensitive to a client’s context, relationships, and lived experience.6,14,19

Paternalism, both systemic and interpersonal, emerges as a powerful undercurrent in these scenarios. Institutional norms, medico-legal concerns, and hospital protocols often presume that Western biomedical knowledge represents the gold standard, implicitly suggesting that deviations from recommended care are misguided or unsafe.6,14,22,23 This perspective reinforces a hierarchical model of knowledge, dismissing the legitimacy of a client’s cultural or experiential ways of knowing.6,14,23 When midwives equate protocol adherence with ethical practice, they unintentionally override client decisions, impose their own values, or dismiss a client’s right to choose care outside the recommendations.8–10 Such actions, even if well-intentioned, are rooted in paternalism and directly conflict with the midwifery model of relational autonomy, which centers the client as a capable decision-maker embedded in their own social, cultural, and emotional world.6,14,19

These dynamics are compounded by a broader climate of professional scrutiny and fear of liability.22,24 When a client’s decision does not align with institutional expectations, midwives must navigate the nuances between legal accountability and ethical care.10–12,14 Balancing national and professional guidelines and hospital protocols with client-centered care becomes especially fraught when a client makes a decision perceived as “risky.”8–10 In these moments, midwives often lack a formal framework to guide documentation, interprofessional communication, or follow-up care planning, increasing moral distress and leaving midwives vulnerable to criticism.11,12 This absence of structural support can create situations where midwives, in spite of valuing relational autonomy, feel compelled to default to defensive or coercive practices.10,12,14,25

Internal emotional experiences, such as fear, uncertainty, and moral distress, further complicate these challenges.25,26 While midwives are trained to center autonomy, they also carry a deep sense of professional responsibility and benevolence.26 When a client’s choice contradicts a midwife’s understanding of best practice, it can elicit ethical tension: a desire to respect autonomy may be at odds with a perceived duty to protect.24,25 This distance is exacerbated by professional cultures that equate liability protection with strict adherence to national and professional guidelines, leaving little room for individualized care or values-based negotiation.11,25 In the absence of reflective frameworks, this emotional burden may push midwives away from relational autonomy and care and toward more directive approaches.10,12,14,25

Midwives’ own beliefs and values also influence how informed choice is practiced.11,14,25 While midwifery emphasizes relational care, even within this model, provider perspectives can unintentionally shape how information is presented or how support is offered.8,9,19 This is not a critique of individual midwives but a call for ongoing self-reflection.6,14,25 Ethical self-awareness of one’s own biases, fears, and values is crucial to fostering respectful people-centered care that truly centers the client’s voice.6,26 It invites a shift from unconscious paternalism to intentional partnership and ensures that relational autonomy is not only an aspirational ideal but an active, sustained practice.6,14,19,25

In summary, the complexities surrounding a client’s choice to pursue care outside of recommendations are amplified by the lack of structured frameworks and clear guidance. Midwives are left to navigate these ethical and professional tensions without consistent support, increasing the risk of stress, resulting in some resorting to defensive and coercive practice, and ultimately leading to poor care.10–12,25 Without institutional reinforcement of relational autonomy, even the most well-intentioned midwives may struggle to uphold the care values of midwifery practice.

EXISTING FRAMEWORKS

Research in Australia has proposed frameworks that offer valuable insights into supporting informed choice when clients choose care that differs from clinical recommendations. However, these frameworks are not directly transferable to the Canadian context because of differences in healthcare systems, models of midwifery care, and professional scopes of practice.5,27,28 Jenkinson et al. (2015) introduced the Maternity Care Plan (MCP), a documentation tool intended for obstetricians to initiate when a client chooses care outside established guidelines.27 While the MCP was designed to promote transparency and facilitate risk communication, its restriction to obstetrician initiation embeds a hierarchical structure that excludes midwives from equal participation in care planning. This structure not only diminishes the professional autonomy of midwives but also undermines the principles of relational autonomy, which emphasize collaborative decision-making grounded in trust and mutual understanding. Furthermore, inconsistent implementation of the MCP raises concerns about variability in its application and the potential for coercive practices that undermine client autonomy.27

Jenkinson et al. (2018) later proposed the Personalized Alternative Care and Treatment Plan (PACT) framework, a document that can be initiated by the client and any obstetric care provider.28 Although more inclusive in theory, the requirement for obstetrician review and approval reinforces the existing power imbalance, diminishing the roles of midwives within the Australian healthcare system. The PACT document is also not well-described in the literature, making the necessary and sufficient documentation vague and uncertain.28

In spite of these limitations, both the MCP and PACT frameworks contribute valuable elements toward a relational model of care.27,28 These include the use of respectful and rights-based language, emphasis on informed decision-making processes, promotion of interprofessional communication, and acknowledgement of ethical and emotional complexity of care provision.23,26–28 These components reflect an evolving understanding of autonomy as relational, situated within ongoing dialogue, interpersonal connection, and contextually informed trust.6,14,19

Nonetheless, neither framework provides a comprehensive, systematic approach that supports all obstetric care providers, particularly midwives, or includes explicit decision-support tools and documentation procedures.11,27,28 In the Canadian context, where midwives often act as the most responsible provider, this gap is especially noticeable.5,7,8 In response, we propose a midwifery-focused framework, developed specifically for the Canadian healthcare setting. Grounded in the principles of relational autonomy, it seeks to support transparent documentation, facilitate ethical and collaborative dialogue, and offer Canadian midwives a tool for navigating complex care planning alongside clients.11,14,19,25

PMCP: A RELATIONAL FRAMEWORK AND TOOL FOR COLLABORATIVE DECISION-MAKING

The proposed framework and decision-support tool, the PMCP, address gaps in supporting informed, values-based care when clients choose care outside recommendaions.10–12 Designed for use by midwives and clients, and relevant to other obstetric care providers, the PMCP fosters transparent, ethical, and collaborative decision-making rooted in the principles of relational autonomy. It facilitates communication within the midwife–client relationship, across midwifery teams, and with the broader healthcare system, while also aiming to mitigate the ethical and emotional strain midwives may experience when navigating complex informed choice discussions.10,25,26

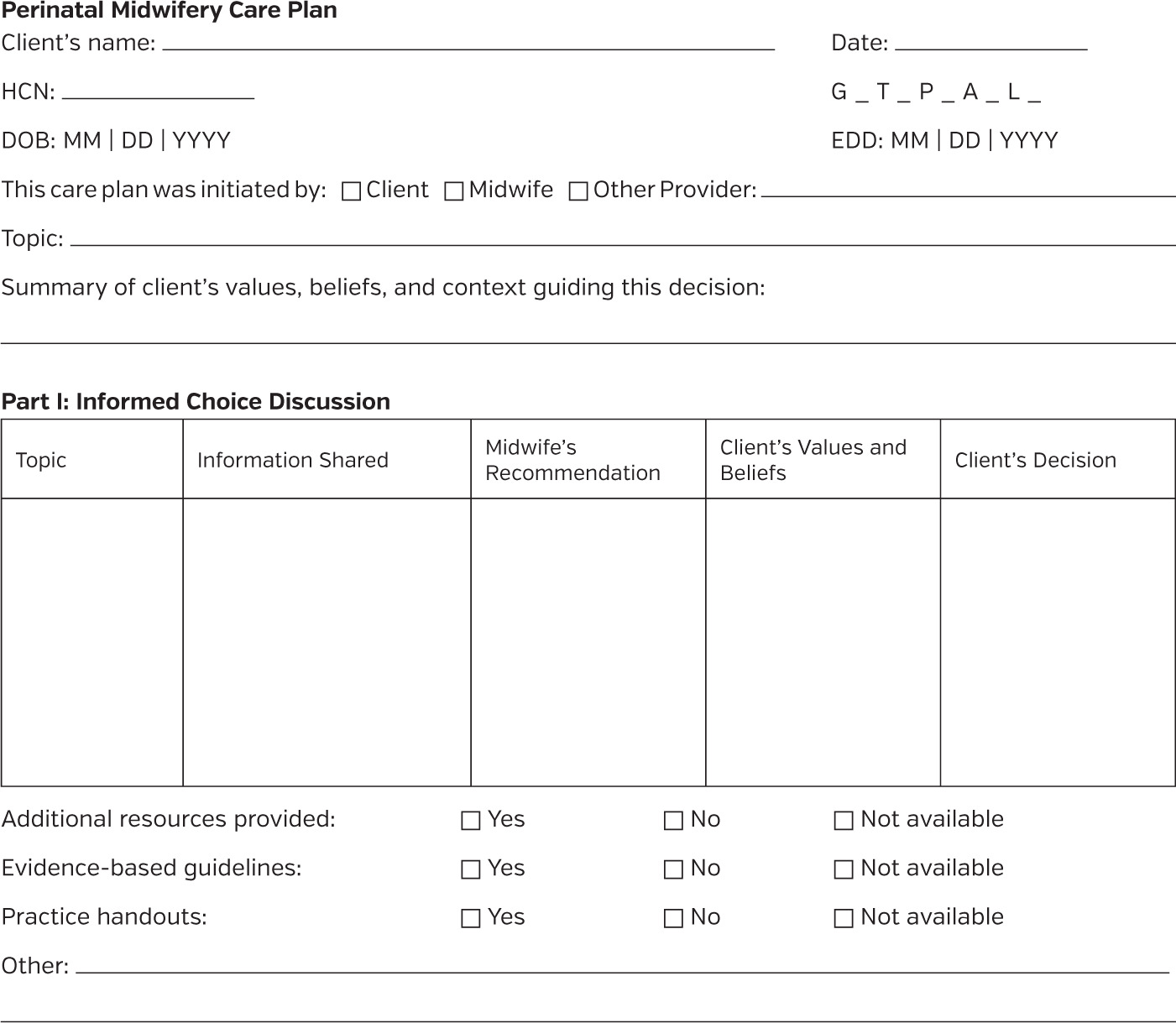

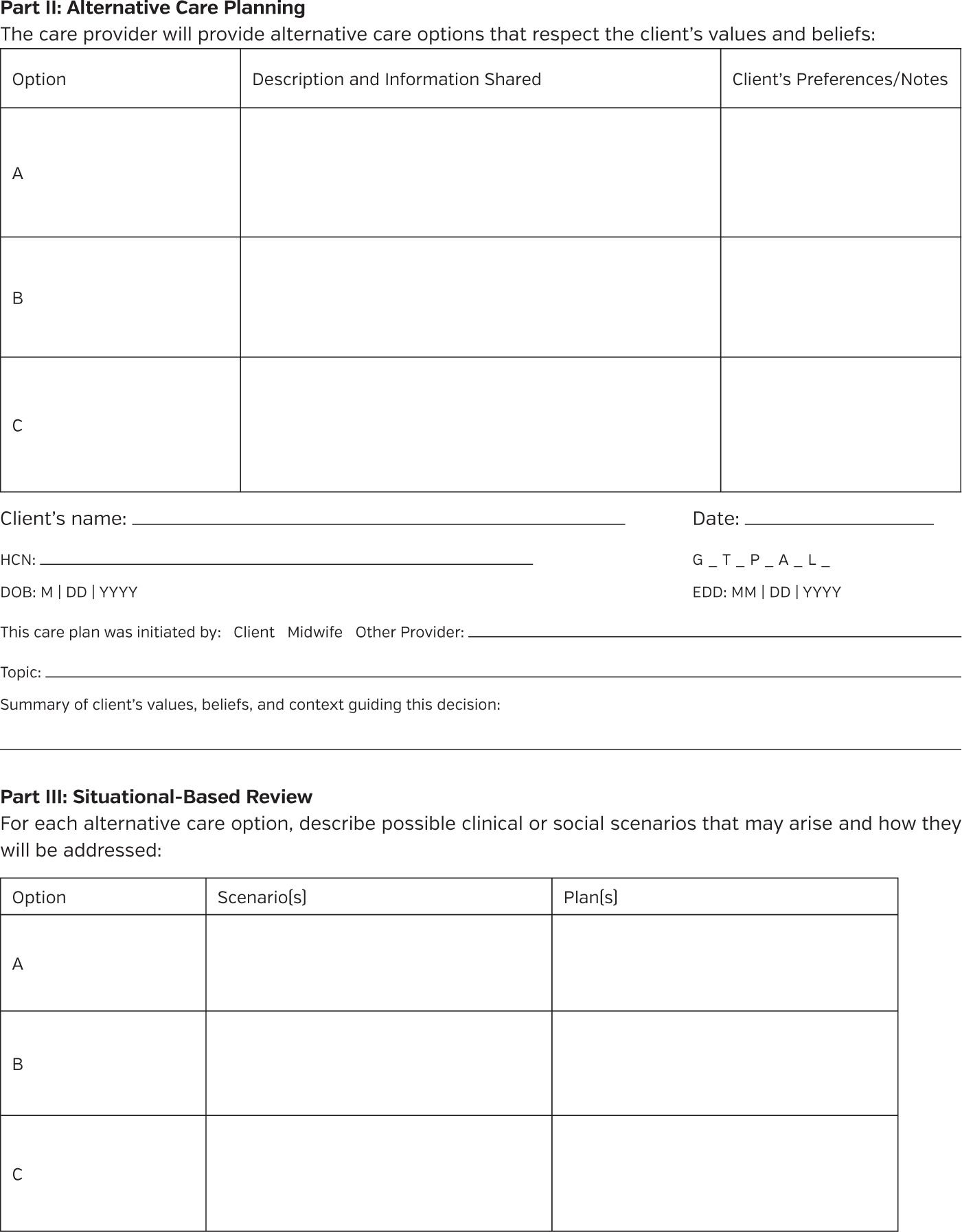

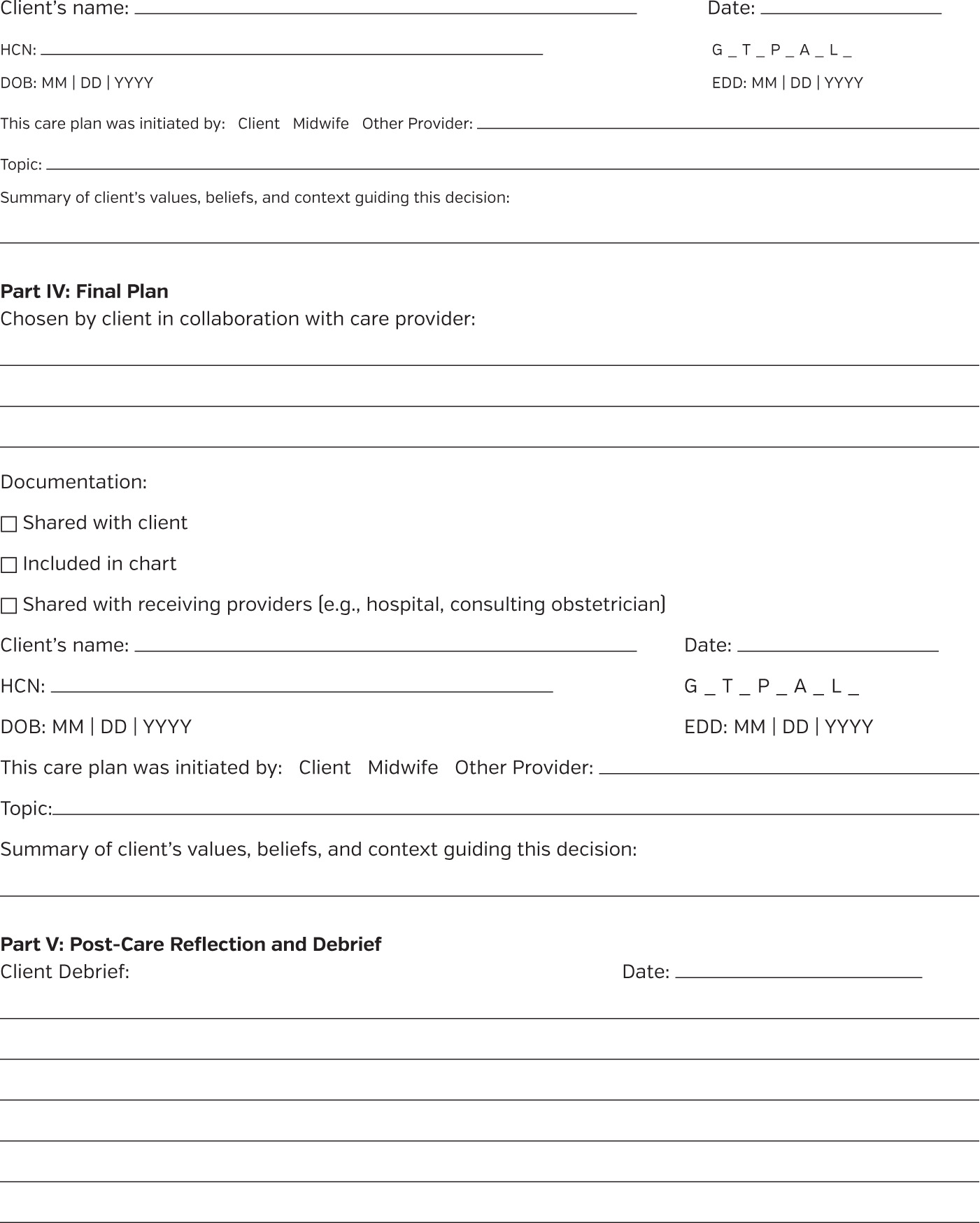

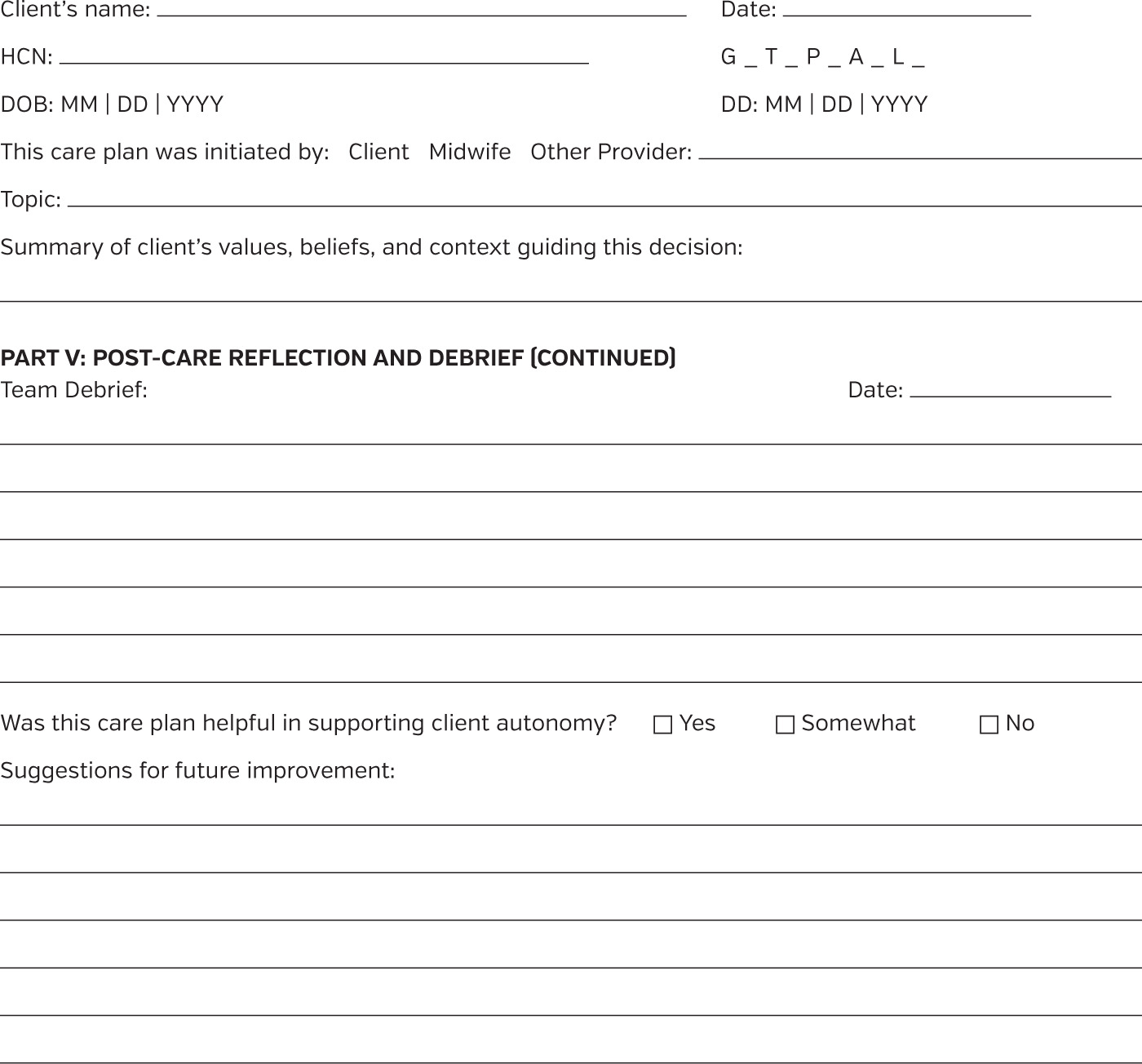

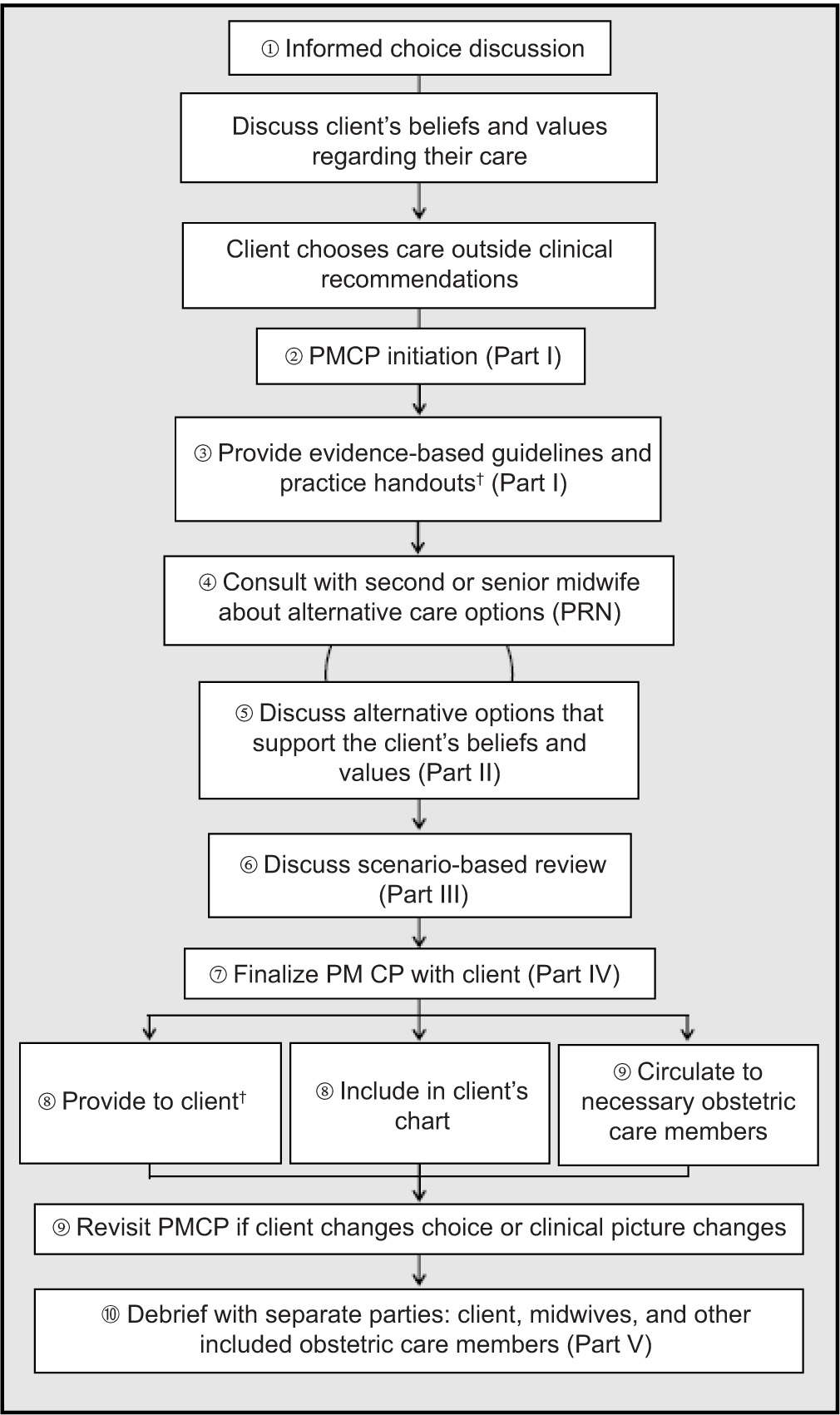

The PMCP comprises two key components: a 10-step framework for collaborative care planning (Figure 1) and a corresponding documentation tool that supports midwives in recording the process (Appendix A). Together, these components guide midwives through complex decision-making encounters in a structured, value-driven, and transparent manner. To illustrate how the framework functions in clinical practice, we present an example of a client who chooses not to use ultrasound for intrapartum fetal health surveillance.

Figure 1. The Perinatal Midwifery Care Plan (PMCP). Outlines the 10-step framework with references to the accompanying documentation tool in parentheses. Accessible for client based on language, cultural and resources barriers. PMCP: Perinatal Midwifery Care Plan; PRN: as needed.

Step 1: Values clarification and informed discussion. This foundational step operationalizes relational autonomy by creating space for clients to articulate their beliefs, values, and lived experiences. For example, a client may express their decision not to use ultrasounds in labor based on a desire to avoid their fetus being exposed to prolonged sound waves. The midwife explores these values while providing evidence-based information and recommendations about intrapartum fetal health surveillance.

Step 2: PMCP initiation. If the client chooses not to use ultrasounds for intrapartum fetal health surveillance, either the midwife or the client may initiate the PMCP. In Part I of the document, the midwife records the initial informed choice discussion and the rationale provided by the client, ensuring that the values shaping the decision are clearly documented.

Step 3: Resource sharing and accessibility. The midwife provides accessible, evidence-informed resources tailored to the client’s needs, such as handouts on intrapartum fetal health surveillance. Materials are selected with attention to language, literacy, cultural relevance, and technological access to support equity and understanding.

Step 4: Alternative care option development. The midwife consults with a second or senior midwife to discuss alternative care strategies that may align with the client’s values. For a client choosing not to use ultrasound in labor, alternative options such as the use of a pinard or fetoscope could be explored.

Step 5: Informed discussion of alternative care options. The client and midwife engage in a second informed choice conversation to explore alternative options. This dialogue is documented in Part II, reinforcing the client’s role as an active decision-maker in their care. For a client choosing not to use ultrasound in labor, the risks and benefits of each alternative option should be discussed, such as the alternatives aligning with the client’s beliefs and the efficacy of each device in the second stage of labor.

Step 6: Scenario-based discussion. For each alternative care option the client approves, clinical scenarios are explored, such as efficacy of the pinard or fetoscope when using hydrotherapy or indications for ultrasound (e.g., abnormal fetal heart rate on auscultation, labor augmentation with oxytocin, and hospital protocol when using epidural). The responses are discussed and documented in Part III. This supports proactive planning and ensures both parties are prepared for varying outcomes.

Step 7: Finalization of PMCP. The client’s chosen plan is documented in Part IV.

Step 8: Communication and documentation. The PMCP document is then integrated into the client’s chart and shared with relevant care providers. For a client choosing not to use ultrasound in labor and planning a hospital birth, this could be included in the client’s hospital chart, to ensure continuity and reduce misunderstandings during labor.

Step 9: Implementation with flexibility. The PMCP document guides care but remains open to revision should clinical circumstances or client preferences change, supporting the dynamic nature of decision-making throughout care.

Step 10: Post-care debriefing. After the care plan has been implemented, the midwife facilitates structured and separate debriefs with the client, other midwives, and interprofessional team members in Part V. These discussions provide space for reflection, reinforce relational learning, and support continuous improvement in care delivery.

The PMCP offers a midwifery-led, Canadian-specific, and ethically grounded approach to care planning that centers relational autonomy.6,14 By integrating values clarification, interprofessional collaboration, contextual scenario mapping, and structured documentation, it supports clients and midwives in navigating complex decisions with clarity, respect, and trust.11,27,28 The PMCP reinforces the client’s right to make informed decisions while equipping midwives with the tools to engage ethically, reduce coercion, and foster shared accountability in care relationships.6,10,16,25

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE PMCP AND FRAMEWORK

The PMCP and its associated framework were developed in response to persistent challenges midwives face when supporting informed choice, particularly when a client selects care that differs from clinical recommendations.10–12 Although informed choice is a foundational principle of Canadian midwifery, implementing it in practice remains difficult in these situations.4,5,11,12 Midwives often navigate these conversations without formal documentation tools or institutional support, leaving them vulnerable to professional scrutiny and other ethical complexities.12,25,26 These challenges are exacerbated by systemic pressures, including protocols, time constraints, and fragmented care systems, that can limit the space for nuanced, values-based discussions.10,11,25,26 The PMCP offers a structured and relational approach to navigating these complexities.

A significant strength of the PMCP is its grounding in relational autonomy, which reframes decision-making as a process shaped by relationships, social context, and mutual respect.6,14,19 In contrast to models that prioritize compliance with clinical guidelines, the PMCP creates space for clients to articulate their values and goals while providing midwives with a clear, stepwise framework for guiding discussions and documenting care.7,11,10,25 In doing so, it addresses one of the core tensions in informed choice: how to support a client’s autonomy while also ensuring that care is ethically sound, informed, and professionally accountable.12,14,25 By embedding documentation within the decision-making process, the PMCP helps mitigate the burden of proof that often falls on midwives when care deviates from institutional norms.11,12,25

The PMCP also addresses the emotional and cognitive demands of supporting informed choice in ethically complex scenarios.11,12,25,26 Its structure encourages midwives to consult colleagues, engage in self-reflection, and proactively plan for clinical contingencies, all of which can reduce feelings of isolation or moral distress.26–28 Furthermore, by providing a clear record of the client’s values and preferences, the PMCP facilitates interprofessional communication and improves the likelihood of continuity during consultations, transfer of care, or shared care.11,27,29,30

In educational contexts, the PMCP offers a pedagogical bridge between theory and practice.11,19 Less experienced midwives report discomfort and fear navigating informed choice, particularly when clients choose care outside recommendations.10–12 The PMCP can serve as a practice-based tool for learning how to engage in these discussions respectfully, ethically, and effectively.11 Its alignment with the CAM’s model of informed choice and adaptability across provincial jurisdictions further supports its applicability within diverse clinical and regulatory contexts.4,5

However, the PMCP does not resolve all the systemic and structural barriers midwives face.11,27 Time remains a critical constraint. Comprehensive informed choice discussions, particularly when clients hold views or make decisions that differ from clinical guidelines, require time and emotional labor that may not be feasible in fast-paced or under-resourced environments.10–12 When clients express care preferences late in pregnancy or midwives do not discuss potential emergent situations earlier, the feasibility of completing the PMCP in full may be limited.

In addition, while the PMCP supports values-based care planning, it relies on equitable and accessible communication to be effective.4,7,11 Clients with limited health literacy, nondominant language fluency, or those navigating intersecting barriers such as trauma, racism, or marginalization may find the process less accessible without additional supports.25,31–33 Midwives must be attentive to these inequities and adapt the PMCP accordingly, but the tool itself does not inherently resolve these access barriers.14,26

Another key challenge is the potential for bias in how care plans are documented. Without critical reflection, the way risks or alternatives are described could unintentionally reinforce coercive or paternalistic dynamics.10,14,25,26 The PMCP assumes a level of midwife self-awareness and cultural humility that cannot be guaranteed without ongoing education and institutional commitment to equity-oriented care.31–33 Documentation alone cannot substitute for ethical competence.6,14

Moreover, the PMCP’s effectiveness as a communication tool is limited in settings where other care providers or institutions do not recognize or engage with it. While system-wide uptake could enhance interprofessional collaboration and continuity of care, the PMCP was developed first and foremost to strengthen midwifery practice and can function effectively as an internal guide and standalone document for midwives.27,30 Even without broader adoption, including the PMCP in the client’s chart can support clarity, documentation, and respectful care planning. In summary, the PMCP offers a structured and ethically grounded approach to navigating informed choice in midwifery care, addressing the challenges midwives face when clients choose care that diverges from recommendations. Its successful implementation does not depend on collective adoption across the healthcare system, though such uptake would be a welcome enhancement.6,11,31,33

CONCLUSIONS

In Canada, quality midwifery care and informed choice are inextricably linked.4,5 Yet, research shows that the quality of care may be compromised when clients choose a path that diverges from clinical recommendations.8–10 Ethical tensions often arise in these moments, particularly for newer or less confident midwives, who may face uncertainty around professional accountability, documentation, and legal scrutiny.10–12,25 These challenges are compounded by a learning model that relies heavily on experiential exposure, leaving significant gaps in preparation for navigating complex, values-based care planning.10,11

As Canadian midwifery continues to evolve, there is a pressing need to ensure that clients’ informed choices are not only acknowledged but actively supported. This requires equipping midwives and midwifery students with the tools, language, and structural backing to engage in care planning that is both ethically rigorous and relationally grounded.10–12,19 The proposed PMCP and its accompanying framework offer a structured, stepwise approach to facilitating collaborative dialogue, exploring shared understanding, and documenting care in a way that reflects both clinical reasoning and client values.

To advance this work, research into the root causes of midwives’ stress when clients choose care outside recommendations could reveal institutional, personal, and cultural factors that undermine informed choice. In parallel, in-depth evaluation of the PMCP’s usability, acceptability, and impact on interprofessional communication and client outcomes is needed. Midwifery-led focus groups and clinical pilot testing can help refine the tool’s implementation and inform adaptation across diverse practice settings.

The changing landscape of midwifery care in Canada demands renewed commitment to informed choice, not as a legal formality, but as a relational and ethical practice.6,14,19 The PMCP and its framework represent an important step toward that vision, offering midwives a concrete means to uphold autonomy, foster trust, and provide safe, respectful, and individualized care.10–12