BACKGROUND

Perinatal loss is a life-changing experience for parents and families. Perinatal loss is defined as the death of a fetus weighing 500 g or more. Death may occur through loss of pregnancy by miscarriage, early loss (less than 20 weeks), or neonatal loss (newborn through 28 days of life).1–3 In brief, perinatal loss is an unintended pregnancy loss between the period of conception and birth of a baby, up to 28 days of life.

The perinatal death rate in Canada is 5.7 per 1000 births.4 Although the death rate is relatively low in Canada, it is high globally. In 2019, the estimated global death rate was 13.9 per 1000 births.5 Women aged between 25 and 29 years have a 15–27% chance of perinatal loss, peaking to 75% in women aged more than 45 years, with a higher risk for women who have lost a previous pregnancy.6 Causes of perinatal loss include congenital abnormalities, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), asphyxia, and trauma.7 Regardless of the cause, perinatal death elicits a distinct form of grief.

Perinatal bereavement pertains to parents’ sorrow following a neonate’s death. According to Fenstermacher and Hupcey, the depth of sorrow may be indicated not by the number of weeks of pregnancy or by the length of the baby’s life but by parents’ dreams—their sense that they were already parents.2 When perinatal death occurs, the effect extends beyond the parents; it transcends to significant others, community members, and health professionals. Caring for bereaved parents and families is an immensely challenging obligation. Perinatal loss presents spiritual, psychological, social, emotional, and physical challenges to families.3 Painful and mixed feelings—including grief reactions, such as anger, sorrow, and numbness—have adverse effects on bereaved parents and their families (siblings, grandparents, uncles, and aunts).8 Bereaved parents and families are likely to suffer from sleeping and eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, chronic diseases, depression, and low quality of life.9 Additionally, it can result in guilt and strained relationships with significant others.10 Over time, some bereaved parents and families learn to live with the loss, whereas others live with chronic grief.11,12 Health professionals play a significant role in helping bereaved parents and their families throughout perinatal loss.

Perinatal loss often occurs within the professional environment of midwives. Midwives are licensed health practitioners trained to provide primary care to patients during pregnancy, labor, birth, and postpartum.13 Midwives also respond to families going through perinatal bereavement, but their training in this area is not extensive. As a result, midwives face challenges in managing perinatal loss.

Midwives form close relationships with parents and families during pregnancy, birth, and postpartum; the relationship shapes how midwives grieve about perinatal loss and manage tasks and their time.14,15 How midwives cope with the challenge, their own grief, and manage family care after perinatal loss may not be experienced by parents as supportive. For example, Watson et al. conducted a survey of experiences of families with pregnancy and infant loss in Ontario, Canada, and discovered an overwhelming number of bereaved families felt that the midwives and other healthcare professionals lacked the skills required to appropriately care and support them.16 Bereaved parents and families grieve differently; some require to be left alone, while others appreciate someone being with them. In 2016, Williamson explored midwives’ management of perinatal loss in a maternity hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa, and found midwives provided families with the choice of either being left alone or having someone around them to support and comfort them.17 Thus, providing choice allows midwives to support them appropriately. Consequently, because midwives focus on the successful delivery of infants, they often forgot about the clients who choose to grieve alone due to high workload and inadequate knowledge on perinatal bereavement care.17

Further, Montero et al. examined the experiences of Spanish health professionals, including midwives and nurses, in situations of perinatal loss as well as the strategies for managing perinatal loss.18 The study revealed that health professionals focused on physical care while ignoring the emotional aspects of perinatal loss. In managing loss, some midwives adopt maladaptive coping strategies, such as denial, self-blame, and disengagement.18 In contrast, others employ adaptive coping strategies, such as realistic appraisal and directly confronting the situation.15

One maladaptive strategy is prioritizing physical care, a midwife may react distantly and coldly toward the patients, denying the severity of loss of patients, especially in early pregnancies.17,18 That results in a lower quality of care for such families.18–20 A considerable number of studies conducted in the United States, Ireland, Australia, and the United Kingdom on management of perinatal loss by midwives concluded that midwives experienced a variety of difficulties in providing perinatal bereavement care, including feeling unprepared.21–24 The challenges confronting midwives need to be addressed to enhance their professional competencies in managing perinatal loss, because they have first-hand encounters with mothers and families regarding care provision during labor, delivery, and postpartum.

Conversely, there are midwives, known as bereavement midwives; they specialize in supporting families with perinatal loss, and are specifically trained in perinatal bereavement care. A preliminary review of the literature about bereavement midwives revealed that such midwives are specialized in offering practical and emotional assistance to mothers and their families during perinatal loss.25 Bereavement midwives work closely with other health professionals to provide empathetic and responsive care to families experiencing perinatal loss. Fullerton et al. describes this essential role of bereavement midwives as supporting and caring for families during their most traumatic periods.26 Although bereavement midwives play a critical role in perinatal bereavement care, not much is written about them. Caring for emotional and psychological needs of bereaved patients is a global concern.18,19 Therefore, it is imperative to reveal the role of bereavement midwives. The purpose of this scoping review was to bring to light the unique role of bereavement midwives and the critical need to incorporate their services for better perinatal bereavement care.

Bereavement Midwives

Bereavement midwives are specialized midwives with additional training, they provide emotional and practical care to families who have experienced perinatal death. Bereavement midwives work exclusively with families to assist them navigate the grieving process and provide support.27 The concept of “bereavement midwife” originated in the United Kingdom, where the profession has been recognized as a specialized midwife practice since the 1990s.27 The role was created in response to a paucity of specialized support available to families following perinatal loss as well as the recognition that midwives could have a significant function in delivering holistic perinatal bereavement care.28 Training for bereavement midwives often includes both theoretical and practical components, such as legal and ethical concerns surrounding infant loss, various types of bereavement care, and the psychological, emotional, and social effects of infant death on families.27

Bereavement Midwives versus Death Midwives

Bereavement midwives are registered midwives with additional training in perinatal bereavement care focusing on providing support to families who have experienced perinatal death. Bereavement midwives are employed by the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom and are recognized as a specialty midwifery profession.28 Some studies have shown that their services can have a positive impact on the well-being of bereaved parents by alleviating anxiety, depression, and PTSD in families who have suffered perinatal death.28,29 However, bereavement midwives are a scarce health profession in the majority of countries.

Conversely, death midwives, more commonly known as end-of-life doulas or death doulas, are nonmedically trained individuals who provide emotional and spiritual support to aid in the creation of a serene and dignified end-of-life journey for individuals and their families and not specific to perinatal loss.30 Death midwives first emerged in the United States in the early 2000s. They are currently found in countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand and can be trained in a variety of ways, including end-of-life care.31

In Canada, death midwives are not regulated or licensed.32 There have been legal challenges to the practice's acceptance and regulation. Throughout history, the concept of midwifery has existed. The term “midwife” is a protected title that can only be used by those who have completed all required education and training to become certified midwives. Because the term “midwife” has a specific meaning and suggests a certain degree of expertise in giving care and assistance to women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, it is used in this context. Therefore, it is not surprising that an appellate court in British Colombia ruled to prevent the use of the term “death midwife” in 2020.32,33 While bereavement midwives and death midwives have a common goal of providing compassionate care to individuals and families experiencing end-of-life or perinatal death, they have different concentrations.

METHOD

Scoping reviews provide an intellectual synthesis of what is known about a topic and allow authorities to make evidence-based decisions.34–36 In order to ensure a strong foundation for the technique, the Arksey and O’Malley five-step framework was used.34

The following questions informed this review:

Primary review question

-

What is known about the practices of bereavement midwives and additional service they provide?

Secondary review questions

-

What is known about the training and education of bereavement midwives?

-

What do bereavement midwives do differently from other professionals?

-

Why should organizations employ bereavement midwives?

Identifying relevant articles

Relevant articles include both peer-reviewed and “grey” literature appropriate to answering the review questions.34 A comprehensive literature search was conducted on the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) databases, and Google Scholar. The databases were searched to find relevant articles using the following search terms: “Bereavement midwife,” “Bereavement Midwife AND Practices,” “Bereavement midwife AND Role”. Grey literature was discovered by conducting searches on the Google Scholar and webpages.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles describing bereavement midwives, and their practices and services were included. To achieve a wider scope, no limits on the date of articles or their geographic region were set. Articles about bereavement midwives’ roles, practices, training, and their impact on managing perinatal loss published in English were included. Articles were excluded if they focused on other health professionals or were not written in English.

Article selection

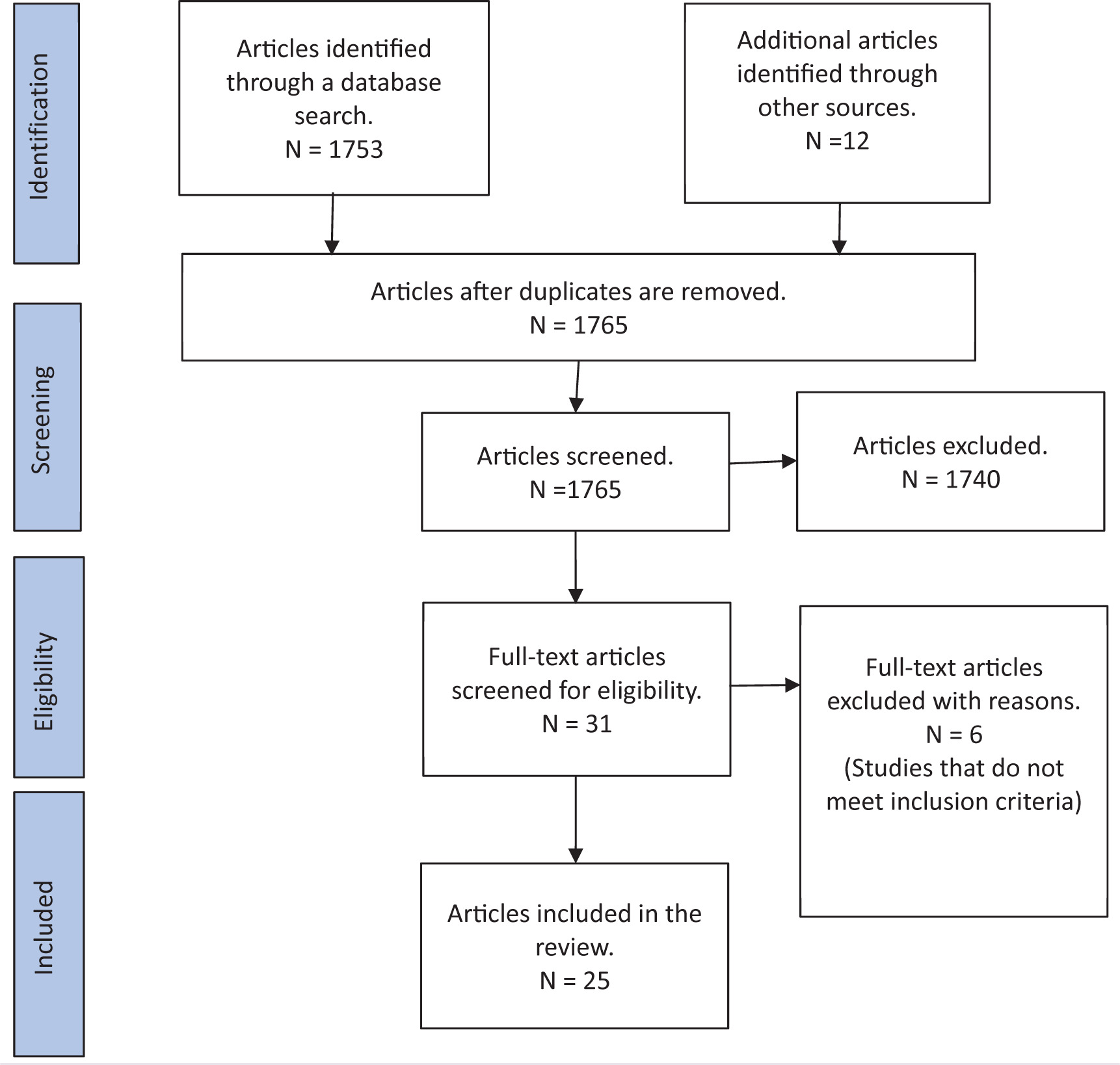

In order to organize identified articles, all publications were exported to Mendeley’s reference manager. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligible articles; duplicates were removed. Then a thorough review of the retained articles was carried out.34 Finally, the reference lists of retained articles were screened to find potentially useful but missing articles.34 The article selection process was documented on a PRISMA ScR diagram.37 A PRISMA ScR diagram depicts the entire process of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of articles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary of Article Selection Process

Charting the data

Tables and figures are created to record the included articles’ critical characteristics and relevant information based on the review questions.34 Following were the critical characteristics: authors, date of publication, origin, study purpose, population, key findings, study design, country of origin, aim of study, sample size, measurement method, and conclusions.34 A display table was used for ease of understanding, highlighting important data (see Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Articles

| Author(s) and year | Title | Country of Origin | Purpose | Research Design | Non-studies (Literature Reviews, Audits, Descriptive Studies, and Opinion Articles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaw (2009)38 |

A Day in the Life of a Specialist Bereavement Midwife | UK | To describe the duties and daily activities of a bereavement midwife | Descriptive article | |

| Banerjee et al. (2016)39 |

Factors Influencing the Uptake of Neonatal Bereavement Support Services – Findings from Two Tertiary Neonatal Centers in the UK | UK | To evaluate the use of bereavement support services in two tertiary neonatal units (NNU) and to investigate the factors that influence it | Quantitative analysis of data | |

| Wilson et al. (2015)40 | Holding A Stillborn Baby: The View from a Specialist Perinatal Bereavement Service | Australia | To record parents’ experiences and results after viewing and holding a stillborn infant at a hospital with a perinatal bereavement service | A cohort study of 26 mothers and 11 fathers who experienced a stillbirth | |

| Power et al. (2016)41 | Clinicians in the Classroom: The Bereavement Midwife |

England | Examines the function of the bereavement midwife and covers a bereavement midwife’s training sessions | Report | |

| Power et al. (2017)42 | Life after Death: The Bereavement Midwife’s Role in Later Pregnancies | UK | Follows a bereavement midwife into the clinical environment to examine her role in supporting bereaved families through subsequent pregnancies as well as the resonances of a second-year student midwife, who spent time with the bereavement midwife in her specialist antenatal clinic and peer support group, the “Butterfly Group” | Peer review article | |

| Ford et al. (2013)43 | Heartlands Hospital’s Bereavement Midwifery Services Team Was Named Best Hospital Care at the 2013 Butterfly Awards | UK | To highlight the award received by the bereavement midwifery team for quality service | News article | |

| Verling et al. (2016)44 | The Experience of Perinatal Palliative Care in a Large Tertiary-Referral Maternity Hospital | UK (Ireland) | To examine perinatal palliative care is the planning and delivery of supportive care throughout life and end-of-life care for a baby and family in managing life-limiting conditions | A retrospective review from 2012–2015 | |

| North Cumbria Integrated Care Foundation Trust (2020)45 | Meeting a Specialist Bereavement Midwife | UK | A bereavement midwife was interviewed about her role, experiences, and advice for anyone who has experienced baby loss | Published interview | |

| Mills et al. (2016)46 | Marvelous to Mediocre: Findings of a National Survey of the UK Practice and Care Provision in Pregnancies after Stillbirth or Neonatal Death | UK | To gather awareness of existing UK practice and experiences with care in pregnancy following the death of a baby | Cross-sectional surveys, including 138 UK maternity units and 547 women who had an experience of UK maternity care in pregnancy after the death of a baby | |

| Henderson and Redshaw (2017)47 | Care after Birth |

UK | Summarizes the findings of the third perinatal confidential investigation conducted as part of the MBRRACE-UK program, focusing on term, singleton, intrapartum stillbirths, and intrapartum-related neonatal fatalities | Report | |

| Bakhbakhi et al. (2019)48 | Parent 2 Study: Consensus Report for Parental Engagement in the Perinatal Mortality Review Process | UK | To create basic concepts and guidelines for parental involvement in perinatal mortality review | A two-round Delphi technique was used: Round 1 featured a national consensus workshop, and Round 2 comprised an online questionnaire with 22 participants | |

| Author(s) and year | Title | Country of Origin | Purpose | Research Design | Non-studies (Literature Reviews, Audits, Descriptive Studies, and Opinion Articles) |

| Johnson (2018)49 | Bereavement Midwives Have a Vital Role in Improving Bereavement Care | England | To describe the educator’s role of bereavement midwives in ensuring quality bereavement care | Descriptive article | |

| Helps et al. (2020)50 | Impact of Bereavement Care and Pregnancy Loss Services on Families: Findings and Recommendations from Irish Inquiry Reports | UK (Ireland) | To describe the impact of bereavement care provided to families during pregnancy and early infant loss as described in 10 public inquiry reports relating to Irish maternity services | Thematic analysis of 10 relevant inquiry reports | |

| Alghamdi and Jarrett (2016)20 | Experiences of Student Midwives in the Care of Women with Perinatal Loss | UK | To investigate the perspectives of final-year student midwives when caring for women who have experienced perinatal bereavement | A qualitative descriptive study. Two focus groups with 10 final-year BSc (Hons) Midwifery students | |

| SANDS (2012)51 | SAND Position Statement; Bereavement Midwives | UK | To explore the role of bereavement midwives in providing bereavement care to a parent with baby loss | Audit report | |

| Award-winning bereavement care (2014)52 | Award-Winning Bereavement Care | UK and Ireland | To describe an award system and training funding established by a bereaved parent for bereavement midwives | News article | |

| Abigail's Footsteps (2021)53 | Bereavement Training | UK | To describe the training available and undertaken by bereavement midwives | Descriptive article | |

| Hughes (2013)54 | Antenatal Care in Pregnancy Following a Stillbirth | UK | To discuss the effects of a past stillbirth on prenatal care in subsequent low-risk pregnancies | Literature review | |

| Strauss (2020)55 | My Journey to Becoming a Bereavement Midwife. The Perinatal Loss Centre | Australia | Midwife’s description of her journey of becoming a bereavement midwife | Descriptive article | |

| IMAGE (2020)56 | A Day in the Working Life of Bereavement Midwife |

UK (Ireland) | Sarah Cullen, a clinical midwife specialist in bereavement, highlights her role as a bereavement midwife at the National Maternity Hospital | Descriptive article | |

| Abramson (2019)57 | Coping with Baby Loss as a Midwife | UK | To describe the critical need for specialist bereavement training and care | Opinion article | |

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (2021)58 | Bereavement Midwifery Support Service | UK | To ascertain additional services provided by bereavement midwives | Descriptive article | |

| Ford (2016)59 | Midwives Trained in New Bereavement Support Techniques | UK | To assess the effectiveness of eye movement training in reducing the intensity of grief among bereaved parents | News article | |

| National Health Service (2020)60 | When a Pregnancy Goes Wrong | UK | To describe how a team of bereavement midwives at Saint Mary’s assists bereaved families | Descriptive article | |

| SANDS (2017)61 | Audit of Bereavement Care Provision in UK Maternity Units | UK | To explore the bereavement care provision in UK maternity units | Audit report |

FINDINGS

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

A critical element of a scoping review is synthesizing the evidence and reporting the findings. The purpose of this scoping review was to reveal the role of the bereavement midwives by mapping out relevant literature about bereavement midwives.

Description of selected literature

A total of 25 articles met the inclusion criteria. They included “gray” literature as well as peer-reviewed articles. In all, 23 articles originated in the United Kingdom, with the remaining two from Australia, and were published between 2009 and 2021. Seven articles were research-based: the investigators employed various study designs, such as a cohort study, cross-sectional survey, Delphi technique, thematic analysis, qualitative descriptive, quantitative analysis, and retrospective review. The remaining articles were descriptive (7), audits (2), peer-reviewed (1), news reports (3), published interviews (1), reports (2), opinion articles (1), and literature review (1). Most of the articles were about the role and practices of bereavement midwives. Others highlighted bereaved parents’ satisfaction with bereavement care. Two articles were about awards established by satisfied parents for bereavement midwifery services. One article was a reflection by student midwives after receiving bereavement care training from a specialist midwife and two bereaved parents who shared lived experiences.

Themes

Most authors agreed that bereavement midwives assist in maintaining high standards of bereavement care in all relevant departments that resulted in comprehensive bereavement care and meeting the needs of bereaved families. Some authors suggested that they communicated effectively with the bereaved parents and their families.45,51,52,58 Other authors also suggested that bereavement midwives are trained in bereavement care and equipped to care for bereaved families.49,52,53,55,59,61 Four major themes were extracted from the data: bereavement care training, comprehensive bereavement care, communication, and meeting the needs of bereaved parents.

Bereavement care training

Bereavement midwives receive additional training in loss and grief counselling. The model of care used in practice includes supporting parents in decision-making, fostering attachment, encouraging psychological safety, and providing strengths-based counselling.40,53,59 Ford noted that some bereavement midwives received training in a technique known as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).59 The EMDR technique is based on the idea that eye movements might diminish the intensity of sorrow and other reflections knit with traumatic situations. It is a therapeutic approach that uses directed eye movements during recounting traumatic memories.77 Although EMDR is primarily used to manage PTSD, some bereavement midwives have obtained expertise in this approach to assist families in processing their grief.

Comprehensive bereavement care

It was reported that bereavement midwives used approaches, such as individual care, holistic care,empathetic care, and parent- and family-centeredness when caring for parents and families who experienced perinatal loss.41 It was also reported that families were referred to bereavement midwives immediately after a stillbirth or baby's death was diagnosed. Shortly after the death, bereavement midwives attend with the family to provide early grieving assistance, continuing through the birth, follow-up consultations, assistance in planning future pregnancies, and providing services, such as arranging the death certificate, funeral arrangements, and spiritual support.39,51,59 According to Power et al.,41 one of the roles of bereavement midwife is to provide exceptional antenatal support to women and families who have previously lost a baby.38,58

Communication

Bakhbakhi et al. noted that bereavement midwives shared information with other team members and bereaved parents and served as patient advocates.48 Bereavement midwives also facilitated communication between bereaved parents and their families as well as other relevant health departments.50,51,57 They coordinated by breaking the news, and requested consent for autopsies in a sensitive manner.60 Ford et al.43 reported improved outcomes for parents and families who received bereavement midwife-led counselling after perinatal loss; this was a similar finding in other reviewed articles.37,50,56,58,61

Meeting the needs of bereaved parents

Bereavement midwives are professionals and provide care with compassion, always follow privacy regulations, and are kind and respectful to bereaved parents and their families.50,57 The majority of authors agreed that parents who were involved with a bereavement midwife in their subsequent pregnancy were enthusiastic about the influence of the care on their experience.46,49,50,58,60 Evidence also supports the usefulness of bereavement midwives in educating and supporting other healthcare personnel. Improved outcomes for parents who received midwife-led support counselling were among the benefits of bereavement midwife care.20,43,46,50,56

DISCUSSION

In this scoping review, what is known about the role of bereavement midwives is examined. Also reviewed are the practices of bereavement midwives, their training, additional services they offer, and why organizations should train such midwives. Herein, the findings are discussed guided by the research questions.

What is known about bereavement midwives, and additional service they provide?

The practices of bereavement midwives are identified as management of anxiety, empathetic communication, individualized care, compassionate relationship, antenatal support, empathetic care, professionalism, dedication, parent- and family-centered care, effective coordination, comprehensive holistic care and counselling, and promoting informed consent. These practices were grouped under one central theme: Comprehensive Bereavement Care.

Comprehensive care is focused on the provision of a full range of services. The care is aimed at satisfying parental and family needs. This includes the provider ascertaining the physical, emotional, and social aspects of parents and family, including the community context.61 Rosenbaum et al.62 emphasized the need for comprehensive perinatal bereavement care that meets the physical, psychological and spiritual, or religious needs of parents. Bereavement midwives provide care according to the needs of each bereaved parent.

According to Mead,58 individualized bereave-ment care should be provided to recognize personal and cultural requirements of grieving parents. Bereavement midwives spend time with bereaved parents to learn about their preferences and to assist them with their decisions from the moment their baby dies to funeral plans and follow-up care.39,42.43 Mead58 also noted that for parents’ grief actualization and the gradual transformation of their relationship with their babies from one of presence to remembering, healthcare providers should treat the baby with the same care that they would give a viable newborn. Therefore, bereavement midwives support parents and their families in creating cherished memories of their baby, such as taking footprints, a piece of hair, and photographs. Bereavement midwives ensure that bereaved parents and their families spend as much time with the baby as they desire. Some bereavement midwives do support parents and families in creating cherished memories, and are well equipped, and their focus is to support bereaved parents and their families.

Bereavement midwives provide care with professionalism and dedication; they treat parents and their families with kindness. For instance, they offer nourishment to parents and families. Bereavement midwives support emotions of bereaved parents and employ empathetic communication.43,44 Bereavement midwives also protect and respect privacy and confidentiality of parents. Overall, bereavement midwives establish a trusting relationship with patients in their care by emphasizing the patient’s perspective. These specialized midwives provide professional care for bereaved parents and their families, suggesting that parents applaud bereavement midwives’ professionalism and dedication.42,43

Additional services that bereavement midwives provide include assisting in maintaining high standards of bereavement care in all relevant healthcare departments. They liaise with other staff members, such as chaplains, neonatal/pediatric pathologists, and mortuary personnel. Bereavement midwives also establish working relationships with external entities, such as the registrar of births and deaths, the coroner, local general practitioners (GPs), funeral directors, crematorium managers, and cemetery managers.51 Establishing working relationships allows bereavement midwives to provide parents and families with adequate information and support through the complex process of post-mortem and burial.

Bereavement midwives provide individualized and unique antenatal care for parents who have experienced previous loss to manage anxiety throughout the antenatal period in subsequent pregnancies.42 Anxiety is the body’s natural response to stress, which manifests as fear about the future. Most bereavement midwives use mindfulness.65 Mindfulness is critical for bereaved parents and their families, because they are overwhelmed at the start of their grieving process. Bereavement midwives allow space for emotions of bereaved parents without attempting to change how they feel. The grieving person begins to recognize thoughts, feelings, sensations, and situations that they either want to get rid of or protect themselves from. Eventually, bereaved parents and their families tolerate and accept the emotions associated with grief as part of a larger process.66,67

Bereavement midwives are also bereavement care educators. Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (SANDS) noted that bereavement midwives provide bereavement care pathway programs aimed at improving the quality of care offered by healthcare professionals after the death of a newborn or pregnancy loss at any time.51 The training offered helps other health professionals and student midwives to appropriately care for bereaved parents and families. Further, bereavement midwives conduct educational training sessions and updates for student midwives on supporting bereaved families; they also host information seminars for relatives of bereaved parents on how to support bereaved family members.20,49,53,60

What is known about the training and education of bereavement midwives?

One of the questions for this review was related to the training of bereavement midwives. According to Strauss, no specialized curriculum is mandated for bereavement midwifery.55 Rather, midwives interested in perinatal bereavement care take special courses related to counselling, interpersonal communication with parents and families, breaking unexpected news, theories of grief and trauma, enabling memory-making after a baby’s death, psychological support needs of bereaved parents and families following loss, and engaging parents in the review of their baby’s death. The courses are delivered by organizations, such as SANDS and Abigail’s Footsteps.53,61 Evidence suggests that health professionals, including midwives, might not adequately offer perinatal bereavement care, especially in communicating with bereaved parents and families.60 Bereaved parents should be communicated in a direct and honest manner.62 Specific language should be considered to ensure that it is sympathetic and sensitive. Training of bereavement midwives equips them to effectively counsel and communicate to promote informed decision-making for bereaved parents and families.20,49,53,60

What bereavement midwives do differently from other professionals?

Empathetic communication is a vital part of bereavement care. Mead recommended that bereaved parents must have direct and honest communication from the care provider.58 Compassionate relational care can nurture bereaved parents in a meaningful manner and positively impact their grief trajectory.68 Bereavement midwives validate parenthood of bereaved parents by encouraging them to name their babies and address their babies by name when talking about their babies. Many bereavement midwives also validate experience of bereaved parents and offer them compassionate care and extra effort in caring. For instance, midwives meet bereaved families for debriefing and follow-up in a timely manner. Bereavement midwives support parents and families especially in discussing the cause of death, often overlooked by other healthcare professionals.

Ford stated that bereavement midwives, especially in the United Kingdom, use innovative communication skills, such as the EMDR technique, in which parents perform specific eye movements concurrently.59,74 The technique is based on the idea that eye movements could diminish the depth of sadness and other thoughts linked with traumatic situations when counselling parents and families experience grief. Bereavement midwives use constructively their knowledge in counselling skills and grief theories to communicate with clients and families. Evidence suggests that parents appreciate their communication and counselling skills.49,55,69 When bereavement midwives share information with patients through counselling, they reflect on their values and beliefs. They are aware of their own emotional, physical, and mental responses to experiences of bereaved families.59 As they negotiate the transformational experience of perinatal death together, a relationship is established between bereavement midwives and bereaved parents. Additionally, bereavement midwives advocate for parents and their families and are consulted by other health professionals.70

Why should organizations employ bereavement midwives?

In exploring why organizations should employ bereavement midwives, the identified reasons are that bereavement midwives provide optimal perinatal bereavement care.58 Bereavement midwives liaise and coordinate registration of death and funeral arrangement, relieving families of the burden of combining grieving with other tasks.49 In addition, bereavement midwives also train other healthcare staff on perinatal bereavement care to meet the needs of bereaved parents; parent satisfaction should be the focus of bereavement care.38,49 Therefore, improving client satisfaction is the main reason for which organizations must train and employ bereavement midwives.

Client satisfaction is a metric that indicates the contentment of clients with an institution or entity.71 Client satisfaction is regarded as one of the performance targets of healthcare, and it is directly relevant to the utilization of health service.72 Health organizations assess client satisfaction by soliciting feedback from patients via a range of techniques, including telephone surveys, written surveys, focus group discussions, and individual interviews.64 Bereavement midwives are part of the personnel who are assessed by institutions. Bereavement midwives help to ensure high standards. For example, a team of bereavement midwives in Heartland Hospitals were awarded the 2013 Butterfly Awards for Best Hospital Care. It was reported that the team’s services were based on empathy, fortitude, professionalism, communication, and dedication. Ford noted that bereavement midwives around the world are making history and being recognized for their hard work.59 Further, satisfied parents and families established an award system for exceptional bereavement care to recognize bereavement midwives.56

Burnout is prevalent among midwives.78 High workload was found to be a significant risk factor for burnout in midwives worldwide. Although increasing access to midwifery care is a global priority, the profession’s growth and sustainability are jeopardized due to high levels of burnout and attrition.75 Employing bereavement midwives would reduce the workload on midwives because bereavement midwives would take over perinatal bereavement care, relieving some of the burden on the already overworked midwives, leading to excellent health outcomes, high client satisfaction, and low per capita costs.73,75

Another vital task of bereavement midwives is to support their clients with decision-making. Wilson et al. have found that profound grieving does not equate with poorer mental health of parents who prefer to see and hold their stillborn baby.40 Bereavement midwives offer parents the choice to hold their babies and spend time with babies while supporting parents and families to create positive memories, maintaining mental health for bereaved parents and families. Henderson and Redshaw noted that bereaved parents and families were concerned about how healthcare personnel communicated and supported them, especially with informed consent for post-mortem procedures.47 Bereavement midwives perform an important role in assisting families during the process of post-mortem. Bereavement midwives take different steps to support families throughout this delicate and distressing period, such as ensuring that families understand the process of post-mortem, assisting in obtaining informed consent, and providing continuous support during and after the post-mortem. This can be especially important for healthcare organizations, as it can lead to a reduction in the number of lawsuits.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

A growing body of evidence supports having bereavement midwives in every health establishment because of the quality of bereavement care offered by these specialists.46,50,51 Kurinczuk et al. argued that the availability of bereavement midwives with specific knowledge and understanding of all the necessary components of perinatal bereavement care is critical for maternity units and community settings. However, there are few bereavement midwives, essentially found in the United Kingdom and Australia.75

High-quality bereavement care should be made possible by training existing midwives to decrease stigma and provide respectful care, which includes acknowledgment and understanding of grieving responses and care for physical and psychological demands of perinatal loss.76 Having the option for existing midwives interested in perinatal bereavement care to specialize in this area is critical for optimum perinatal bereavement care.77 After fetal death, optimal bereavement care lowers the negative emotional, psychological, and social impacts on parents.46 It is of enormous benefit to integrate bereavement midwives into health institutions globally to serve as perinatal bereavement care educators and consultants to health professionals who encounter bereaved parents. Finally, it is essential to conduct future studies on bereavement midwives and their impact on bereaved parents and their families. Perinatal bereavement care should be included in midwifery education to prepare midwifery students for their future roles, with the option for them to specialize in perinatal bereavement care.

LIMITATIONS

Although most of the articles referred to in this review were published in English, there is linguistic bias due to excluding articles not published in English. Most of the articles belong to “grey” literature not available in mainstream research publications and as a result some literature on the topic may have been missed as part of this review. As is typical in other scoping reviews, methodological evaluation of the quality of the articles was not performed.

CONCLUSION

In this scoping review, what was known about the practices of bereavement midwives was explored and it provided a descriptive map of the literature on bereavement midwives and their practices. Also, towing to the limited number of research studies on the topic, it highlights the need for continued research on this emerging and unique healthcare role. Such a review is vital because interactions of grieving parents with bereavement midwives profoundly impact their ability to cope with loss, and bereavement midwives offer a unique and specialized role in perinatal loss that is beneficial to families and the healthcare system. It is critical that specialization in bereavement midwifery must be incorporated into midwifery education and that bereavement midwives are integrated into every healthcare system to provide services to bereaved parents after a perinatal loss.